Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

It’s no secret that the Trump administration has moved quickly over the past few months to dismantle diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility programs in both the federal government and the private sector. In a case that’s flown under the radar, the Supreme Court may be about to hand the Trump administration its biggest weapon yet in the fight against DEIA—the possibility of criminal liability.

The Trump administration has used various levers of governmental power to attack recent efforts to diversify institutions. The federal government has culled documents and policies to erase any mention of DEIA (sometimes leading to perverse results, such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration dumping worker safety policies). The Department of Education circulated a “Dear Colleague” letter that (illegally) threatened schools that receive federal funding with the loss of federal funds if they maintain DEIA programs. The president issued (another legally dubious) executive order that threatened the federal funds of institutions that provide gender-affirming care for transgender individuals. The Department of Education (again, illegally) canceled hundreds of millions of dollars in federal contracts with Columbia University based on the administration’s claim that Columbia has failed to combat campus antisemitism. The Department of Defense canceled policies that prohibited contractors from running segregated facilities and ended programs on cultural awareness.

That’s only a partial list. But as these examples suggest, the administration has often relied on federal funding as its weapon of choice in the fight against diversity and inclusion. That is a powerful tool: Every major educational institution receives large amounts of federal funds, and threatening those funds exerts considerable coercive pressure over schools. The same is true for health care facilities, many of which receive federal funds.

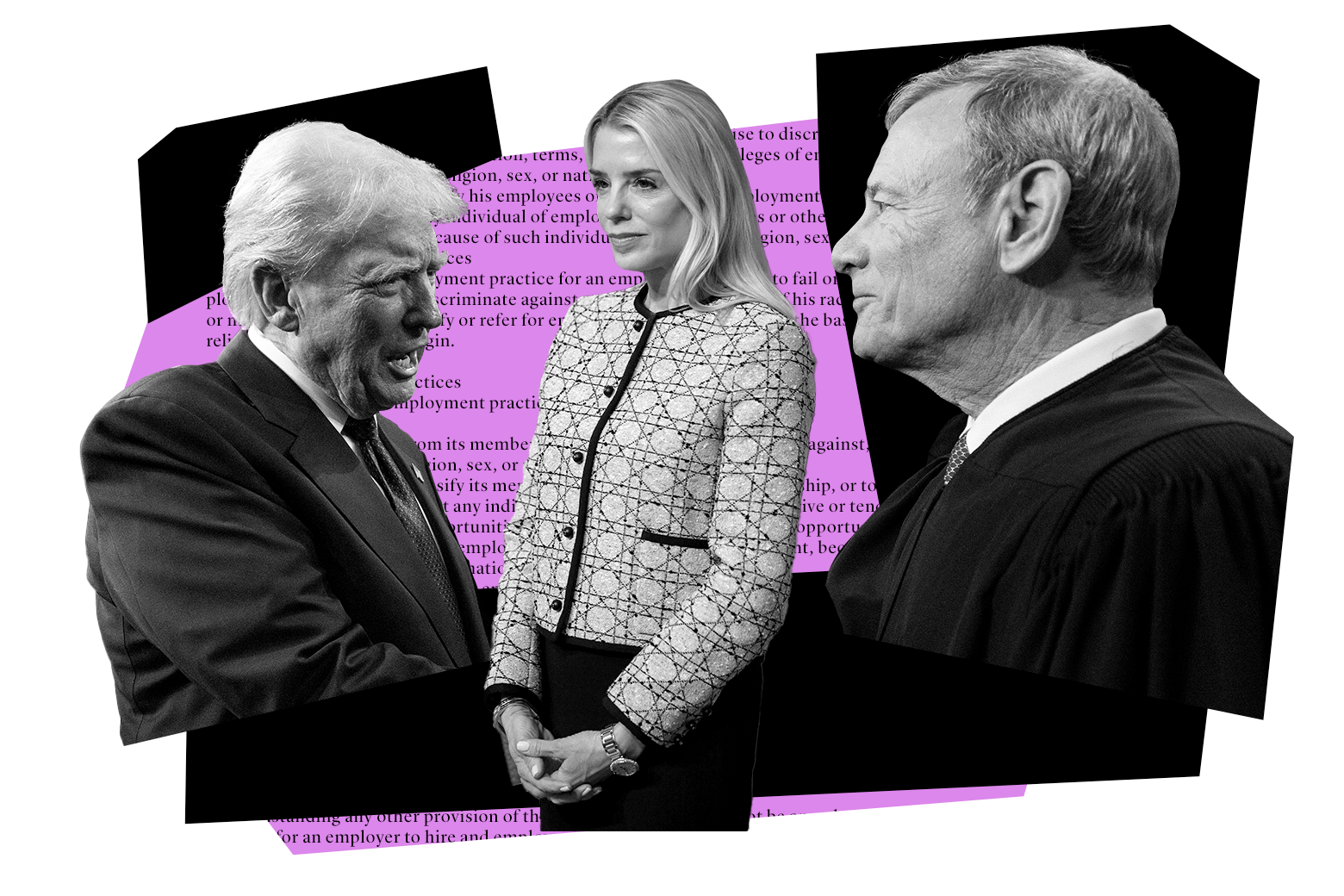

Yet many companies and corporations may not depend on federal funds in the same way that schools and health care facilities do. To get those entities in line, the administration will need something else, such as the threat of criminal liability. Strikingly, the new attorney general issued a memo on her first day ordering line prosecutors to look into potential “criminal investigation” of companies and institutions with DEIA policies, while the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia threatened Georgetown University over its supposed use and teaching of DEIA. Of course, these efforts do not currently pass constitutional muster.

That’s where the U.S. Supreme Court comes in. The court has before it a low-profile case, Kousisis v. United States, that could, if it goes the federal government’s way, offer the federal government a plausible path to criminally threaten some number of individuals and entities that maintain DEIA policies and practices.

Kousisis involves a question about the meaning of the federal criminal laws against wire fraud and mail fraud. Those laws, as their names suggest, generally prohibit using means of wire or mail to engage in fraud.

But what does it mean to engage in fraud? In Kousisis, the allegation is that a contractor who partnered with the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation engaged in fraud by misrepresenting that the contractor would subcontract with minority-owned businesses. The federal government says that’s fraud, whereas the defendant says it’s not because that term in the contract (requiring subcontracts with minority-owned businesses) did not have any economic value—it didn’t affect the price of the contract.

Imagine that the federal government prevails in Kousisis, and can prosecute individuals and entities for allegedly making misrepresentations about contractual terms that do not affect the economic value of the contract. Also imagine that instead of a contract term that required a company to subcontract with minority-owned businesses, there is a contract term that requires the company not to have any DEIA programs or engage in any DEIA practices. The administration could then threaten criminal liability against any entity that has represented in any agreement that they do not have certain DEIA policies or practices based on whatever the Department of Justice deems to constitute such a program.

The Trump administration has already taken a first step toward enabling the criminal prosecution of entities that continue to maintain DEIA practices, at least those that receive federal funds or federal contracts. In an early executive order, the administration required every agency to include “in every contract or grant award” a term requiring the contracting party or grant recipient to agree that it is in compliance, in all respects, with federal antidiscrimination laws—as the Trump administration understands them. And the Trump administration has repeatedly said it believes that federal antidiscrimination law, counterintuitively, prohibits DEIA practices and policies rather than requires them.

No one observing the past few months could question that the Trump administration is intent on dismantling DEIA programs and civil rights in the process. And no one should doubt the administration’s willingness to mine the depths of federal law to find any path to doing so. This past week, after all, the administration invoked a virtually unheard of, and almost never used, provision of federal immigration law to try to deport Mahmoud Khalil, a lawful permanent resident. If Kousisis allows the federal government to launch fraud prosecutions over contract terms with no economic value, we should expect the Trump administration to try to threaten, if not institute, criminal prosecutions as part of its fixation on DEIA.

Kousisis has, thus far, flown under the radar. But the case represents a ticking time bomb in the Trump administration’s aggressive fight against diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.